So when I finally got aboard a ship for the first time, it was in the engine room of a steam ship. I proceeded to befriend the engineer, and work my ass off, build a rep over a few months, and learn what I could. I still regret not going engineer route at times, but I don't have the tolerance for the goddamn heat.

On the next-to-last day of my first 120-day voyage on a ship, I worked outside for the first time. It was hot as balls in the engine room, but as luck would have it, we had just passed Cape Hatteras northbound, and it was April, so it was 68 and sunny outside, and I worked outside sitting about 12 feet up on some piping, chipping rust and enjoying the beautiful day. It was a watershed moment, and I knew I was going to be going deck after that.

Fast forward through 2 years. My life at sea was enough to award me a rating as Able-Bodied Seaman, unlimited (a senior able seaman), as I had 3 times the requirement of 1,080 days at sea, and passed the exam to be rated able, which is pretty much the core Deck General exam that all officers take without the math and details, with a timed hands-on demonstration exam of marlinespike Seamanship besides. I had to splice and tie whatever knots a coast guard bosun's mate wanted while a stopwatch was running. It was fun.

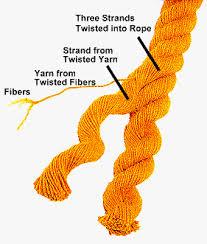

Now, the exams for marlinespike seamanship require only that the evaluee can make about 15 knots on demand and splice (eye, butt or short) 3-strand line. Splicing was something that I could do from my fishing days, so that was no big deal.

My Sea Daddy, Orlando, was a fantastic experienced Able Seaman. A native of Cape Verde, a natural polyglot who spoke seven or eight languages, and who knew how do do any job on the deck of a ship. He was the guy we sent aloft in a bosun's chair, one of the least popular tasks that had to occasionally happened. He taught me a lot and remains one of the finest human beings I've ever met. He also gave me my first Portuguese language lesson, to use on the girl I had met at a wedding, who I later married.

| |

| that's him on the right. |

Manny, the Bosun, was another. Manny is larger than life. He's about 6' 6" or 6' 8", 300ish lbs, and is the strongest human being I've ever encountered. He was in his 60's, but physically looked 20 years younger. He was from Barbados, and had the deep black skin and mellow bass British-accented Carribean accent that is rightfully famous. Imagine James Earl Jones with an accent and you get the idea. For all Orlando's experience, Manny had sailed everywhere for even longer, on old-school style ships- boom-and-stay rigs, the traditional, complicated and difficult work that we avoided thanks to the proliferation of hydraulics. Manny knew his shit.

So it fell on Manny to teach me how to splice hawsers.

Ship lines are different from the rope you see at the hardware store. Instead of what you're used to seeing, 3 strand lines, like this:

We had 8- or 12- or 24 strand lines, like this.

So it fell on Manny to teach me how to splice double-lay rope, like the stuff above. This shit is HEAVY. One man (well, normal man. Manny could) can't drag these lines unaided off off an elevated platform, where they normally stay faked out (laid out for use, not coiled). Splicing involves a hacksaw, duct tape and a wooden fid the size of your lower arm.

This was one of the last things I really had to master before I felt like I was a real sailor, and being able to splice cable- and hawser-laid line, along with being able to stay within about 1/4 of a degree while hand-steering a ship, was an important distinction for us among the unlicensed guys I worked with. There were other benchmarks, like being able to repair a needle gun, reliably work as stopper man when tying up, or 'rigonomics' (being competent at rigging and working aloft), but it was splicing that made me feel like I was finally an experienced merchant seaman.

And hell, there were plenty of lines to practice on.